As the sun makes its steady descent behind the mountain peak on which the tiny Andean village of

Iruya clings, preparations for that evening’s festival have not begun.

“I don’t know if there’s going to be a festival tonight,” says Gloria Federico, owner of Hostal del Café.” The orchestra hasn’t arrived yet.”

The townsfolk don’t seem too worried. Instead, they are more interested in watching the soccer game on the opposite bank of the dry riverbed. One woman sports a bright red cap and jacket over her traditional skirt. She must be rooting for the team in the red uniform.

Who is winning?” I ask her.

“It’s difficult to say,” she says. “It’s too far away.”

During the rainy season, the other side of the river is truly far off. In January and February, torrential rain sends water of the Iruya River rushing through the wide gorge below the town. Furthermore, frequent mudslides cut off the only connection Iruya has with the outside world—a 50-kilometer-long dirt road which curves like a serpent up and over a steep 4,000-meter pass called Abra del Cóndor.

Before it gets too dark, we start to make our return journey to Tilcara where we will spend the night. There will be no festival for us and perhaps not for the villagers either. At each hairpin turn, we look for a sign of approaching headlights in the distance, but we see nothing but the silhouetted peaks around us.

By now the sun has completely disappeared, yet the sky is still a vivid blue and it shines its shimmery reflection in the tiny streams winding through the dark valley.

Just on the other side of the mountain pass, our headlights catch the light of the reflectors of a vehicle parked on the side of the road—its hood open. Three shadowy figures are bent over the engine.

Our driver, Marcelo Cespedes, offers a ride to one of the men. The least we can do is take him to a telephone booth so he can call a mechanic.

“But how far are we from Iruya?” says the man. “We are suppose to play at a festival tonight.”

Cespedes assures him that we’re closer to Humahuaca than to Iruya, so he hops in our car.

Everyone is quiet. Occasionally, the man checks for a signal on his mobile phone without luck.

Over an hour later, we drop him off at kiosk. Perhaps he’ll find someone to take him back toward Iruya tonight, but it’s already late. I have no idea how the real story concludes.

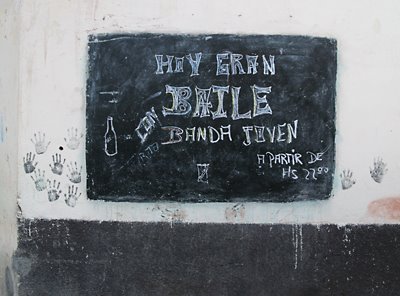

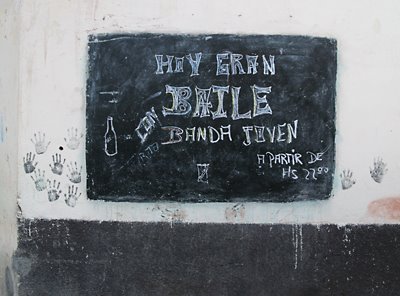

But as we pull away, I imagine a different ending. I envision piling the entire band and their instruments into our car and heading back to Iruya. We arrive just in time for the party to start amid shrieks of joy from the crowd gathered to welcome us. Then we dance the night away under the stars to traditional Andean music by the group called Banda Joven.